I was a terrible tourist in Berlin. Committing to the Berlin Film Festival meant not seeing much of the city. Instead I’d thumb through the Forum and Panorama sections of the catalog over coffee. I chose films and, just in case, back-up films. By bike, foot and U-ban I shuttled between the Delphi, Cubix, Arsenal, Cinestar and Cinemaxx. I waited patiently in line. I always got in.

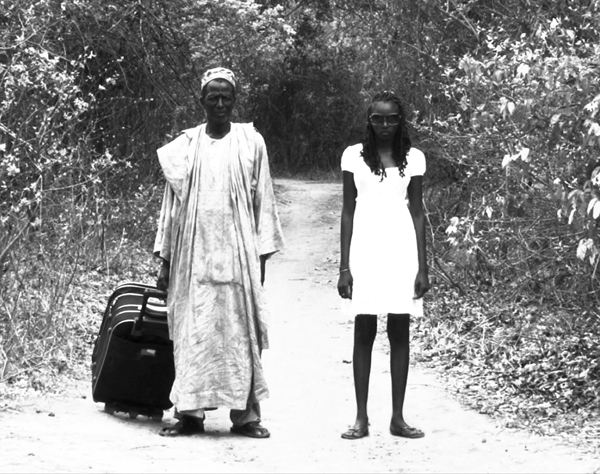

The Battle of Tabatô, shot in Guinea Bissau was the most unusual film I saw.

The pacing and dialogue is curious. For example there are extremely long gaps between the simplest questions characters ask each other and the responses. Often there isn’t an answer at all. A question from the daughter to the father, “where did you meet my mother?” just hangs in the air. The story is a mixture of symbolism and realism that is often impenetrable and mysterious. I felt on unfamiliar ground and I liked that about the film. It turns out the film was made collaboratively with a Portuguese director and the inhabitants of Tabatô, a village known as an important center for music in the region. This collaboration produced an uncanny, visually beautiful film (shot in black and white) about war and peace. Another African standout, Elewani is a South African narrative film centering around the conflict between a young woman and her family. Elewani returns to her home village after graduating university, with her fiancée in tow and a scholarship in hand for graduate studies in the USA. However her father informs her that she is expected to be third wife of the King of the village, an expectation dictated by a culture rooted in important rituals and myth. When she refuses the marriage her parents decide offer her teenage sister to go in her place. To prevent that from happening she accepts the situation. However she does not submit blindly and soon discovers that things are not exactly as they seem.

A favorite of mine was the angst-ridden and often very funny Croatian film A Stranger about a man in the city of Mostar agonizing over whether to attend the funeral of his Muslim friend. He is especially worried sick about what a man named Dragon, ostensibly an important figure in the community, thinks of him. However, Dragon, like Godot, never materializes. The films palpable anxiety, stems from repercussions of the war in the 1990s, and extends beyond the main character to the other characters and all situations. This film also contains a hilarious, exquisitely acted scene depicting the absurd experience of dealing with bureaucracy in a banal office setting — an atmosphere where nothing moves forward and nothing is resolved.

Another film in which nothing moves forward and nothing is resolved is a German film called A Strange Little Cat. It’s a strange little film, precisely choreographed, about a single family in a small space. The quotidien rhythms of the middle-class kitchen are interrupted by odd dialogue and unsettled by ambiguous relationships. The most puzzling character is mother who failing to genuinely connect with those around her emanates a cool unhappiness. She is suffering from something. We can only guess what.

My favorite guilty pleasure was a Brazilian film called Reaching for the Moon, a sweeping bio-pic about Elizabeth Bishop and Lota de Macedo Soares. It’s a lovingly acted, fictionalized account of their affair that moves along lines of Bishop’s poetry.

So wrap up care in a cobweb

and drop it down the well

into that world inverted

where left is always right,

where the shadows are really the body,

where we stay awake all night,

where heavens are shallow as the sea

is now deep, and you love me.

Other films I saw were: Margaret von Trotta’s Hannah Arendt staring an impassioned Barbara Sukowa. Unfortunately about 20 minutes into the film Arendt and her German friends start speaking in their native tongue, leaving their American friends like Mary MaCarthy, (and me) to wonder what the heck they are talking about. A rarity at the festival, there were no subtitles. Hélio Oiticica, is a fascinating collage of archival footage chronicling the artist’s deep commitment to his art and his cocaine. Je suis pas mort is an body/identity switching film with a social message about the future of France wrapped up in a preposterous plot. Here it is: a white middle age guy goes into the body of an impossibly handsome young Algerian and in this body reconnects with his wife. Inch’allah, an audience favorite, is about a pretty Canadian doctor caught up in the Palestinian/Isreali conflict. Materia Oscura is an Italian film about military testing in Sardinia. I was disappointed that Materia Oscura missed its mark as it tried to depict the ravages of military testing on the environment. The contemporary shots of the Sardinian landscape were not visually compelling enough and the abundant military archival footage of bombs exploding is presented at various speeds through a steenbeck viewer. This device is repeated so many times that the images eventually lose their poetry and impact. I thought more could have been made of the connection between the stores of archival footage and the poisons stored in the soil, plants and bones of the inhabitants in the area.

I ended up seeing five American films. Richard Foreman’s first film in 30 years, the opaque Once Every Day was initially a challenge as it is nearly impossible to piece together what may or may not be going on in the film. Finally I simply quit trying and surrendered to the sensuality of the image and sound. A Single Shot, is a taut, back country, gun infused, mumble- thriller, Concussion, is a light lesbian sex drama, not surprisingly, brought to us by the producer of the L-word and focusing on a suburban lesbian turned upscale prostitute for ladies who will pay $800 a session.

I went to one retrospective screening. Ophüls’s Letter from an Unknown Woman. It was a late show and I settled back into my seat, took a sip of beer (which is allowed in the theater, but popcorn is not) and let myself be swept away. A film like this brings me back to my very first experiences with the movies — my teenage years at the Brattle Theater in Cambridge and then as a projectionist for my college film club. Everything I love about the movies is based on a bedrock of Classic Hollywood productions like this Ophüls film and my beloved French New Wave. These primary experiences have defined, and perhaps even limited my tastes. On this viewing of Letter from an Unknown Woman I felt more frustrated with Lisa’s insistent masochism, but I still loved Joan Fontaine as much as ever.

And speaking of love and cinema, on this topic Noah Baumbach’s joyful Frances Ha is a real winner. This is a perfect example of a film I would never see if I was was home in New York. I simply wouldn’t waste the money on a babysitter and deal with the logistics to see a film about a 27 year old woman trying to figure out what she’s doing with her life in NYC (even if I was once that 27 year old myself, and still sometimes feel that way). For this reason it was a perfect film to see in Berlin. If you like Masculin Feminine, which I do (a lot) you’ll probably like Frances Ha. The film may be influenced by the French New Wave but it’s a comedy, something American films have a knack for. Greta Gerwig is very, very funny. She’s Carol Lombard funny! There is some youthful content crossover with the show Girls, but Girls, at the end of the day is just television.

Frances Ha is a movie.